|

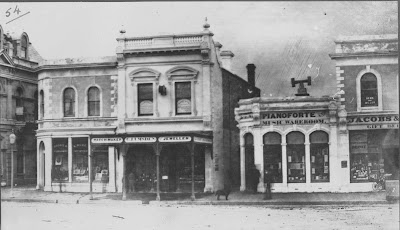

| The Invercargill Post Office and Town Clock. Taken prior to 1908 [Source : www.philatelicdatabase.com/] |

Proving Its Usefulness

1900 - 1943

This continues the story of Invercargill's 1893 'Littlejohn' Town Clock and chimes. You can read from the first part HERE. This third part details the lengthy campaign to have the clock tower raised and the reason for the eventual dismantling and storage of the clock.

In July 1900 comes a surprising report. The Mayor, Mr J.S. Goldie, is reported as having received a telegram from Mr J.A. Hanan, Invercargill Member of the House of Representatives, confirming that he had "interviewed the Minister [of Works] re raising the Post Office tower, so that the clock may be seen and the chimes heard all over the town. The Government are prepared to bear the expense of raising the tower, if the Borough Council or the public will bear the cost of raising the clock." The Council duly agreed to bear their share of the expense.

But raising the tower would apparently not be as easy as first anticipated. In August 1900 the Minister of Public Works writes that he had been advised; "that the brick work is as high as it is safe to take it as the walls and foundations were not designed for a greater weight than has been put on them. The tower could, however, be carried up in timber and brick nogging (not solid brick work), cement plastered on exterior, for some 15ft or so additional, but the clock would require to have seven feet dials to be seen effectively."

The Mayor then advised Council that "Mr Sharp" had informed him "that the building was quite strong enough up to the walls of the tower, above which they were somewhat weak; but still he thought they were quite strong enough to admit of the tower being carried 15ft higher." The matter was referred to the Finance Committee who duly recommended "That the Government be informed that the clock tower can be safely raised 15ft without any public risk."

Mr Hanan advised Council in early September 1900 that he had interviewed the Minister of Works who had handed him a copy of the report on the matter by the Government Architect, Mr Campbell. The latter did not believe there was much advantage in raising the tower but that the chimes might be placed above the clock chamber. This would be at a cost of about £300 "Councillor Stead thought the public would not be satisfied with simply raising the bells, they wanted the clock raised."

In November 1900 Council were advised that the Government would however vote £250 towards raising the tower, again subject to the Council bearing the cost of moving the bells. The Mayor noted that original plans had provided for a tower 25 feet higher but had, it was believed, been reduced due to consideration of cost. The Council would ask the Government for plans of the proposed alterations. In July it was advised that the plans submitted had not been approved by the [Works?] Department and that new plans would have to be prepared. This would, however, lead to a further delay but there the matter appears to have rested as there is no further mention of it.

Just after midday on the 23rd January 1901, the clock, along with church bells, began tolling upon the sad news being received that Her Majesty, Queen Victoria, had died.

In response to an offer by Mr Nicol in March 1901 to install more efficient lighting of the town clock dials at a cost of £42 per annum for five years, a correspondent notes that "the tradesman" already receives £40 a year, that "the illumination is quite good enough for all the distance that the time can be made out on the dials" but notes ruefully that for the price paid there might be an improvement in the running of the striking mechanism; "Every few days or week we have erratic chiming, or, as to-night, none at all; the hour struck mixed up with the chimes or at 15 minutes past the hour... the Council should call upon their servant for an explanation." In actual fact, Messrs Nicol Bros. appear to have charged £25 p.a. for maintaining the clock.

But the clock itself appears to have proven itself an accurate timekeeper. In April 1906 "The Southern Cross" marked the twelve year anniversary of the clock, noting that; "Many doubted its ability to keep the correct time, but it has now lived to prove its usefulness, and if it performs its duty as well during the next 12 years, it will have served the residents well."

In June 1909 the District Traffic Manager of Railways advised Council that "The Department had been in the habit of coveniencing the public by delaying departing trains when the Town Clock was slow, but the discrepancy on the 8th inst. had amounted to eight minutes, and it was out of the question to delay trains that length of time." The mayor advised that he had discussed the matter with "Mr J.T. Peter's" who had kept a man in the tower "to watch the machinery for the purpose of finding out what the trouble was." and to "rectify any fault that appeared." He believed that "the clock had been knocked about" and that unknown persons had removed shot from the compensating balance. It was believed that members of the public were accessing the tower and that a glass casing should also be placed over the main parts of the clock.

In April 1912 a similar problem of irregular timekeeping was noted with the tramways after complaints had been received about the irregular running of the trams which had timed their departure to the Town Clock. But, as the Inspector noted, no trams had left before the advertised time.

In August 1912, and despite Cabinet having voted the sum of £400 the previous July, the Minister of Public Works advised; "that if the chimes are raised as proposed there will be no occasion to elevate the clock itself, and in view of the considerable additional expense which would be involved, it has been decided, after consideration, not to interfere with the position of the clock or dials."

By September 1913 continuing problems with the chimes and of timekeeping caused the Town Council to notify the contractor "that unless the clock is attended to more satisfactorily than it has been for some time the contract will be cancelled and the deposit forfeited." Mr J.T. Peters had been awarded a new three year contract in March 1912 for his tender price of £25 p.a. but as he was now out of town he had sublet the contract to Mr J.S. Roby. The latter was to be notified that the Council intended terminating his contract.

This appears to have spurred Mr Roby into action, replying that he had taken over the clock which he had now "overhauled and put in good order and repair and had it going within ten seconds of time over a period of a week." As Peters advised in Novermber 1913 that he had sold his jewellery business the afore-mentioned Mr Roby was then given the job of maintaining the clock.

In June 1914 the Mayor, Mr D. McFarlane, advised Council that he had written to the Minister of Public Works drawing his attention yet again to the raising of the Post Office Clock tower which, due to building work all around, could not now even be seen beyond the other side of the street; "An objection was formally raised to the proposal on account of the difficulties which would have to be overcome in raising the tower, but Mr McFarlane has stated that it has since been found that the difficulties can be easily overcome."

In July 1914 the Town Council received word that Government had finally approved the raising of the tower by twenty feet and that the matter was now in the hands of the Public Works Department. But with the First World War soon taking precedence the work did not proceed and the necessary funds appear to have subsequently been removed from the Government vote. The last mention of this matter in Council appears to be July 1919.

In July 1919 Council were advised that "the Post Office clock was being interfered with and damaged by small boys who were in the habit of climbing up to the works." A small bomb or cracker was found lying on the floor of the clock room and one of the wire cables that carry the striking weights (which weighed over three cwt.) had been partly cut through. This matter was referred to the "Government authorities" for action. Security in the clock tower does appear to have always been somewhat lax.

|

| The Foundations Under Construction for the New Post Office. Foundation Stone laid 2 Aug 1938 [Source : "The Southland Times"] |

The city council were however advised on the 17th December 1940 that the Government had no objection to the old clock remaining in situ behind the new building, While the clock would largely be obscured from Dee street the chimes would at least still be heard. The new three story Invercargill Chief Post Office building (which I worked in for 18 years), to the design of Government Architect Mr J.T. Mair, would be officially opened by the Hon. Patrick Webb, Postmaster-General, on the 28th July 1941.

But the death knell for the old clock and chimes came as early as 1943 after the Government had decreed that all towers on Government buildings must come down "because of previous experience with earthquakes", a reasoning that was actually quite valid. The Council were then asked to accept the clock and chimes "as the property of the citizens." The clock would now be placed in storage in their old water tower.

Click HERE to read the fourth and final part of this Blog.

Correction of any unintentional errors or additional information welcome. My email link appears in the right-hand menu bar.

Sources :

- Papers Past [National Library of New Zealand / Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa]

- "Centenary of Invercargill Municipality 1871 - 1971" by J.O.P. Watt, 1971 (from my own collection)

- McNab Collection, Dunedin Public Library

- Dunedin City Council Archives

- "The Southland Times"

- "New Zealand's Lost Heritage" by Richard Wolfe, 2013

- Waymarking.com